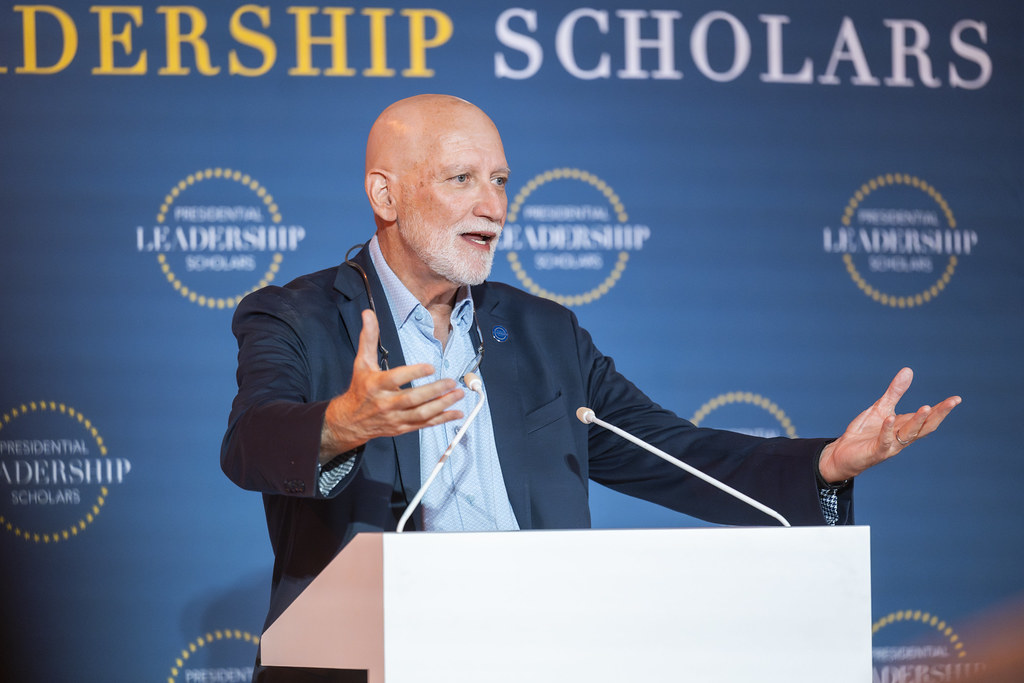

Dr. Mike Hemphill is Co-Director of the Presidential Leadership Scholars program and Senior Director of Leadership Development at the Clinton Foundation. He recently reflected on the creation and evolution of the PLS program, the value and impact of the alumni network, and his hope for the next 10 years of PLS.

Tell us a bit about yourself and what brought you to the Presidential Leadership Scholars (PLS) program.

It’s really an interesting story about how I got connected with PLS. Really it goes back to my time on faculty at the Clinton School of Public Service. My area was communication, organizational communication, leadership, conflict management, and those were things I taught when I came to the Clinton School. Before that, I had spent 24 years at the University of Arkansas-Little Rock on the faculty. We had a very strong metropolitan mission, so it was expected that the faculty would export their expertise to the community wherever it was needed. All those years I was at Arkansas Little Rock, I was working with groups and with organizations on a wide variety of communication issues, just taking this practical approach to communication. How can we take what we know about communication and help people get things done in a more effective way? And so, I had this history of working with groups and helping them work through their communication issues, and it really served me well.

I was in the process of leaving the provost’s position at Centenary College when I had a fateful meeting with Bruce Lindsey [former Chair of the Clinton Foundation Board of Directors] at the bar at the Capitol Hotel. He told me about PLS and asked if I’d be interested in coming back to Little Rock to help develop it and represent the Clinton Foundation’s participation in the program. And I said yes.

With PLS, we were creating this leadership development program that was going to be focused on bringing in people working in a wide variety of areas, facing a lot of different challenges, and then helping them work through the best ways of figuring that stuff out. It just was a really nice fit.

I say this all the time, the last 11 years with PLS have been the most rewarding of my career. I’ve had a great career, but as I look back on these 11 years, it was like this was exactly where I was supposed to be at just that right time.

PLS was born from a first-of-its-kind partnership between presidential centers of different political parties. As you and the team developed the program, what was the original thesis? What did you hope it would accomplish?

From the very beginning, we always described the program as being bipartisan. We had the four presidential centers that were involved. We had three presidents at the time who were actively involved in the program. But what was interesting is that while we described ourselves as being bipartisan, we were also very clear we were not a program preparing people for politics. And so, from the very beginning, we knew this was not a presidential studies program, or a policy analysis program. It was going to be something different. And it was going to be different because we were going to bring a broad diversity of people into the program working on a wide range of issues, trying to make their communities better, however they define their community.

As I look back on it, what was clear, what was guiding us in our work, was the power of relationship in leadership. The relationship between President Clinton and President George H.W. Bush and President George W. Bush in their post presidency was something special that people paid attention to.

What I’ve always shared with the Scholars is that we don’t view leadership as something you do to somebody. Leadership is not a commodity that you have. We don’t hold these presidents up as singular models of leadership. What we hold up are the relationships they cultivated with the people they worked with and the people they served as the basis of their leadership. And that’s what we’re hoping that the Scholars take away from the program. So, all along it was always that idea of relationship and collaboration more than anything else.

Speaking of the presidents, how do you see President Clinton’s influence in the program?

Well, the most obvious way is with his active participation in it. When the Scholars come to Little Rock, we spend time with President Clinton, and it’s not just sitting in the room listening to him talk. We actually have a conversation with him. Over the years, I’ve had the opportunity to moderate a lot of those conversations. It’s kind of neat to hear the president talk about his experiences in the White House, facing what were the toughest challenges on the biggest stage, and talk about them in ways our Scholars can relate to. Then they get to ask questions. And that is just a very special experience for the scholars, and it helps make the program distinctive compared to other kinds of leadership programs.

I think President Clinton also represents the approach to leadership we want to take in this program. He speaks all the time about finding the things we have in common with one another, treating each other as three dimensional characters, and that everybody has a story and that everybody’s story deserves to get heard. He’s able to share that and demonstrate that to the Scholars. And I think that’s powerful too.

And then I’ve got to say, another way he’s an influence is that he’s the best cheerleader for our program. I’ve been in so many situations where he is talking to groups and PLS will come up – he’s always talking about it. You can tell he values the program, he thinks it’s important and that means a lot to all of us.

When the Scholars visit the Clinton Center, they learn about vision and communication through the lens of the Clinton Administration. How do you design the content for the module and what do you hope Scholars glean from the module in Little Rock?

It’s no mistake that we talk about communication and vision when we’re here in Little Rock because that is one of President Clinton’s great strengths. Here are the things we focus on that I think reflect President Clinton’s approach to leadership. One is we take a very strong values-based approach to leadership. We go through exercises in which the Scholars identify, in as clear way as possible, the values that are driving their leadership. We talk about the importance of reflection and thinking about whether what I’m doing right now reflects the things I think are important.

So, while we’re here at the Clinton Center we will look at how President Clinton conveyed the values of opportunity, responsibility, and community. We trace it back to when he was governor and then explore the consistent repetition of those values. We look at an inauguration speech when he was governor, the speeches he gave when he was on the campaign, the New Covenant speech at Georgetown right after he announced he was going to run for president, all of his campaign speeches, every single one of the State of the Union addresses, his two inauguration speeches, and the speeches he’s given since leaving the White House. Whether implicitly or explicitly stated, those values are always there. From a rhetorical perspective, that’s a really important lesson for our Scholars to learn, you do repeat those values because it contributes to people’s understanding of what’s driving you.

It becomes the criteria that you and other people use to evaluate the decisions you’re making. It also demonstrates that your values are authentic. The way you treat people, the way you interact with people, ought to be reflecting those exact same values.

And then the third thing I would tell you that is a reflection of President Clinton is the importance of narrative, the importance of storytelling. Everybody has a story. Everybody’s story deserves to be heard. And I very intentionally, over the course of the program, help the Scholars start telling the story about the work they’re doing, to start thinking about their lived experience and the way they share that with others as a way of finding common ground with them. I hope by the end of the six months all the Scholars understand there’s real value in telling their story but also of encouraging others to share their story with them. And that’s clearly something that they get from President Clinton every time he talks with them.

You’ve built relationships with nearly 600 Scholars at this point. How do Scholars continue to collaborate after the six modules, and what makes the PLS alumni network so special?

You cannot underestimate the impact of the six-month program. That’s been the most surprising thing to me, how consistently the experience of those six months affects the Scholars in the cohort in all sorts of different ways. The insights they gain about themselves is astounding to me because these are people who are accomplished and already have a track record of leadership that’s impressive. But there’s something about this experience that we curate in PLS that shows them something about themselves that they didn’t realize or were maybe on the verge of realizing it. PLS has a way of just making that even clearer. And the other thing is the relationships they develop with one another in the cohort. We bring together people whose paths would never have crossed otherwise. It’s incredible to see how they come together and develop friendships, support one another, and how quickly that happens.

A couple years ago, I had an alum tell me, “Here’s the thing about PLS. You don’t have very many opportunities after the age of 40 to develop meaningful friendships with other adults.” And he said PLS was just this treasure trove of new friendships. I had never thought about it that way, but those new friendships happen every year. So, here’s why that’s important, every year you have 60 Scholars who have that experience, and then they’re added to a network of Scholars who’ve also had that exact type of experience in the previous years. When we bring alumni from different cohorts together, you can see them introduce themselves to each other and you can see how quickly they’re connecting and how deeply they’re interacting about stuff in a very short order. It’s a valuable asset that the program’s able to produce, and I think that’s what then contributes to their ability to work with one another. We have examples of Scholars who have discovered they have mutual interest and start working with one another. The things that are even more interesting to me are the more spontaneous moments, like when somebody sends up the “bat signal” to other alumni saying they need help with something, whether personally or professionally. Within minutes they’ll get responses from people they’ve never met before. I think it’s the shared program experience that makes the connections easier, more comfortable, and more trustworthy.

PLS is celebrating its 10th anniversary this year, and you’re retiring at the end of the year. What is your hope for the future of PLS?

I guess my hope for the future is to keep on keeping on. It’s more important now than it’s ever been to have a program like PLS. I believe we live in a different time now, where people confuse obstinance for leadership. And I think there’s a real need for us to bring established leaders together to learn and to better understand the importance of collaborative leadership.

As I think about the next 10 years for PLS, it’s critical for us to share the stories of the work our alumni are doing that illustrate the value of collaborative leadership. And I hope we can find ways of engaging our alumni even more effectively than we do now. Our alums are a powerful group of folks. They have a bond with each other, even with those who weren’t in their cohort from across the years because they have this shared experience. We see examples of where they’re able to partner with one another. But I hope over the next 10 years, we find ways of really amplifying their work, holding up their work as examples for others, but also helping them to connect with each other even more effectively.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.